GEORGE LOIS 2005 MPA SPEECH

I stand before you, an unrepentant adman, dressing down the illustrious magazine establishment of America. I’m here to talk about your boring, adoring, butt-kissing magazine covers. My lone credentials are creating a decade of Esquire magazine covers during “the Golden Years of Journalism” in the ‘60s.

In 1962 my ad agency, Papert Koenig Lois, was spearheading the watershed event in advertising known as ‘the Creative Revolution.” That’s when Harold Hayes, Esquire’s editor, first approached this Bronx-born, Greek American 30 year-old advertising art director for advice on how to create a great cover. When I met Harold Hayes for lunch at the Four Seasons restaurant, he was stylishly decked out in a white suit (pre-Tom Wolfe and pre-No Smoking law), waggling a skinny stogie in keeping with his getup, Southern drawl, and poker-playing eyes. I told him that every “package design” should be at least as good as the product inside – and I thought his Esquire of the past six months had been the best magazine product I had ever read. As promising as the publication had become under Hayes’ leadership, readership was stagnant and the magazine remained financially troubled. I told him, “You don’t get great stuff from Baldwin and Capote and Talese with group-grope stumbling over each other, voting for the safest syntax!” “Sounds great pal,” said Harold Hayes, “But don’t tell me…do!” and begged me to do just one cover. So I did.

Based on pieces on the upcoming heavyweight championship bout, I showed Floyd Patterson, an 8-to-1 favorite, lying alone in the ring, left for dead, seemingly killed at the hands of challenger Sonny Liston. Arnold Gingrich was appalled that my cover was calling the fight a week before fight night and said so in his publisher’s page, denouncing my prediction, my design style, and my hubris – but Harold threatened to bolt if he rejected it, proving to me that the trombone-playing Southern liberal who was also a Marine Reserve officer was one rare bird. When the October 1962 Esquire hit the newsstands, the prediction became the laughingstock of the sports world. But when Liston destroyed Patterson in the first round, doubling the highest newsstand sales in the history of the magazine, Harold truly believed, and that was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

During the turbulent ‘60s, I produced 92 covers for Esquire. Every time a new visual editorial was delivered to Harold from my drawing table, Esquire’s publishers, editors, ad salesmen and assorted bureaucrats crossed their hearts and fingers. After doing the first three covers I had sent him without prior warning, I started to telegraph my cover concepts to Harold, usually over the phone – while it was Harold who sometimes suggested the subject. We spoke in shorthand and communicated with economy. For Christmas, Harold pleaded, fingering his pencil stogie, “Ol’ buddy, ya gotta give these ad sales guys something they understand, Y’all gotta give me a goddamn Christmas cover!” “You got it!” I swiftly replied.

So, in those days of rising racial tensions and Black Revolution, I decided to depict America’s first black Santa: Sonny Liston, the meanest motherfucker in the world, the last person anybody would want coming down their chimney on Christmas Eve. Respirators were rushed to Esquire’s ad offices.

To dramatize a hilarious piece on the open romancing on the set of ‘Cleopatra,’ I slipped the billboard painters at the Rivoli Theatre 20 bucks each to touch-up the enormous cleavage of Elizabeth Taylor, with Richard Burton admiring the charms of the titular Queen of Egypt.

In 1965, pre-Friedan, Steinem and Abzug, I spoofed the upcoming Woman’s Movement by slapping shaving cream on the beautiful blond Italian actress, Virna Lisi (no American beauty had the balls to pose for it) – and she took it off on the front cover of America’s leading men’s magazine, signaling the sexist war soon to follow.

The day after Ed Sullivan introduced the Beatles to America on TV, I put a Beatles wig on his head and he grinned ear-to-ear like Ringo.

For a college issue, when I composed a composite of the men I chose as the leading heroes of American college youth in 1965 – Bob Dylan, John Kennedy, Malcolm X and Fidel Castro, divided by a cross-hair, right-wing America went ballistic!

Three years before news came of the My Lai Massacre, for an issue that featured John Sack’s account of an infantry company from basic training to ‘Nam, I lifted a cry of pain from a young G.I. – “Oh my God, we hit a little girl!” – and set it starkly in white against a funereal black background. When I asked Harold how badly we would piss off America, he said, “If they don’t like what’s on our cover, they can always buy Vogue, sweetheart.” That was 1966, a premature time for indicting what became America’s longest and wrongest war (until now).

When my how-to cover suggesting a tactic young Americans could use to fake-out the draft board, rock legend Jimi Hendrix told Esquire the cover had inspired him to fake being gay to be thrown out of the army!

When a critical piece was being written on Humphrey for parroting his boss, I sat a Hubert dummy on a ventriloquist’s knee. The front cover fold-out revealed a smug LBJ. It was a needed jab at a good man’s failure to speak out against the Vietnam debacle. When the article wound up being laudatory, Hayes added a compromising “But in fairness to our Vice President, see page 106,” because he couldn’t bear to lose the cover.

For one issue, an unexpected request came from Harold. “They’re clamoring for a girlie cover,” he pleaded. Even though I had told Harold I would never do a T & A cover, I swiftly replied, “You got it!” I showed a naked dame, squashed in a garbage can to illustrate a story headlined “The New American Woman: Through at 21.” “Well, pal,” was Harold’s reaction, “you sure didn’t disappoint me.”

For a piece on Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald, witnessed live by millions, I re-enacted the tamest events on kids’ TV that day.

“Do a job on Svetlana,” he asked. “Oh, no,” I moaned. “Not another magazine cover with her rat fink mug! I don’t care who her old man was – you never knock your old man.” Thus it came to pass that I scribbled her father’s mustache on Svetlana Stalin; the family resemblance was awesome.

When Roy Cohn wrote a self-serving book on his slimy years with Joe McCarthy, I shot him with a tinsel halo, visibly self-applied to his noggin. Oblivious to its slashing irony, Cohn posed obligingly. The next day Harold called me: “Oh, you really nailed that sonofabitch.”

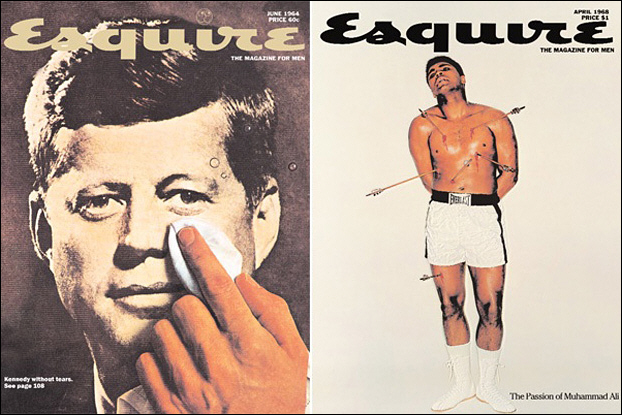

And Harold knew he’d find himself in deep, deep water when I showed the maligned Muhammed Ali reenacting the martyrdom of St. Sebastian, stripped of his boxing title and sentenced to prison for refusing to fight in a bad war. Harold lined up his fine Carolinian nose against my Bronx schnoz and put his Dixie neck on the chopping block once again. The Esquire cover of a man that redefined American heroism, hung in thousands of college dorm rooms and became an instant icon symbol against the war that would claim more than 58,000 American dead before our last choppers fled Saigon.

And then there was Nixon. Before he ran for president in 1968, I showed him being made up like a movie star. “Nixon’s last chance,” was my caption. “This time he’d better look right!” Promptly, Harold got an indignant call from Ron Ziegler complaining that Esquire was trying to depict his boss as a homosexual. Huh?

When I showed our three assassinated leaders, John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King in a haunting apotheosis, standing on the sacred ground of Arlington National Cemetery, Harold took a deep breath – and America gasped.

For an issue on the decline of the American avant-garde, when the image of a Campbell’s soup can became the symbol of the new Pop Art movement, I showed Andy Warhol drowning, literally, in his own soup. Andy wanted me to trade my original art for one of his Brillo boxes, but I told him I could get a real Brillo box at the A&P for nothing!

When I perpetrated a sham sighting of the illusive Howard Hughes, the media crowd fell for it, not realizing it was a put-on. Huh? Esquire’s publisher and ad department went apoplectic. Harold merely chortled.

When Harold sheepishly told me his publisher begged him for a “beautiful people” cover to appease a men’s fashion account, I figured, why not? In my estimation, the three most attractive new male celebrities of 1968? Clean shaven Tiny Tim, Michael J. Pollard and Arlo Guthrie! Hayes keeled over laughing.

When I slapped an Easy Rider movie marquee on St. Patrick’s Cathedral to illustrate an article on “Movies, the Faith of our Children,” Harold did the sign of the cross and took the heat. Cardinal Cooke was not amused.

When Norman Mailer and Germaine Greer were feuding, my take on it was to show Mailer going ape for the female-liberationist doll, and vice versa. Macho Mailer challenged me to a fistfight but I refused, telling him he had to qualify first by taking on Germaine.

But the cover that truly tested the mettle of Esquire’s staff (and indeed, the mettle of America itself) was a portrait of Lieutenant Calley, in the flesh. There he was, awaiting trial for his ordering the My Lai Massacre, posing with an obscene grin, surrounded by Vietnamese children, oblivious to any connection between the kids he murdered and the ones he was posing with. I’m always asked why in the world he stood still for it, and I admit I used my credibility as a Korean vet to con the infamous army officer. My subversive message was that Calley’s assumed lack of guilt was a stupid innocence shared by those that insisted that America, then as now, never “cuts and runs.” After receiving the cover, Harold called, as he always did after the smoke cleared. With a deep sigh, he gave me the verdict: “Most detest it, George. But the smart ones love it.” “You going to chicken out?” I asked. “Nope,” he said. “We’ll lose advertisers and we’ll lose subscribers, but I have no choice. I’ll never sleep again if I don’t muster the courage to run it.” After one of his college campus lectures, Harold said about the Calley cover, “The kids are having fistfights over this one, Lois. It’s great!”

Obviously, Esquires’s brass put up with my shenanigans (all deadly serious) because during those Hayes years circulation went from 500,000 and approached 2,000,000 (dumping back to 500,000 when Hayes and I bailed out).

Equally important as sales, especially to Harold Hayes, his brilliant New Journalism writers, his editing and designing staff, and me, was our effect on the nation: the Esquire of the ‘60s was a culture-buster – inciting outrage with a dozen anti-Vietnam covers that infuriated the establishment and inspired the idealistic younger generation. Hayes et al. dealt with the torrid issues of race, war and politics, blasting the silly pretensions of Pop Culture and deflating the synthetic images of celebrity.

Harold called them “Pictorial Zolas.” The covers outraged the mighty, angered advertisers and infuriated readers – but to the youngest and the brightest back then (many of you sitting in this audience today), they visualized the changes in America and needled hypocrisies. Creating covers that startled, provoked, even offended, helped a new generation to discard the hypocrisies of the ‘50s, as they were admired and collected by the wired-in young who became the cultural movers and shakers of the next two decades.

The ubiquity of the celebrity profile in popular magazines since the Hayes era continues to be fawning psychobabble based on a 15-minute interview over caffe latte, glorified by yet another kiss-ass magazine cover that sits unsold at the newsstands. Just a few years ago, James Wolcott wrote in Vanity Fair, “Although the audacious covers Lois designed for Esquire in the ‘60s are lauded as one of the marathon achievements in magazine history – the industry-wide testimonials are nothing but talk – because today, more than ever, magazines have never played it safer.” The fact is, that for the last forty years, the magazine community has never understood the overwhelming message of my covers: that the editorial content and imagery of a great magazine belongs to the passionate writer and iconoclastic graphic designer and heroic editor – and not to outraged advertisers or quivering sales departments of the celebrity flavor of the month whose butt you’re kissing, or to your readers, and certainly not to cranky letter writers!

People ask me all the time why there aren’t any more great magazine covers like Esquire of the ‘60s. I tell them there are three glaring reasons. Number one, the magazine industry long ago joined the wild goose chase of sycophantic celebrity coverage, resulting in a forest of mindless magazine covers. Number two, nobody asked me. And three, I tell them because there ain’t no more buccaneering bad boy editors like Harold Hayes.

For those editors and editorial designers who are handcuffed by their self-imposed insistence on sicko-fan covers (accompanied by a cacophony of story lines), who take comfort in the belief that “idea” covers cannot sell in today’s media culture, why doesn’t one brave, talented editorial team in this audience go to work and change the face of magazines by proving what I know to be true: Great magazine covers with big, edgy ideas that make powerful statements about America’s politics and culture – through wit, irony, and even ambiguity – can force-feed an irresistible taste of a magazine’s content and, issue after issue, create a titanic stir in the American psyche.

George Lois is one of the most creative and prolific admen of our time. From 1962 to 1972, he changed the face of magazine design with his 92 covers for Esquire magazine.

FAJARDO, Puerto Rico (AdAge.com) – Below is a transcript of the speech made by George Lois to the Magazine Publishers of America session of the American Magazine Conference on October 18, 2005 at the Conquistador Resort & Spa.