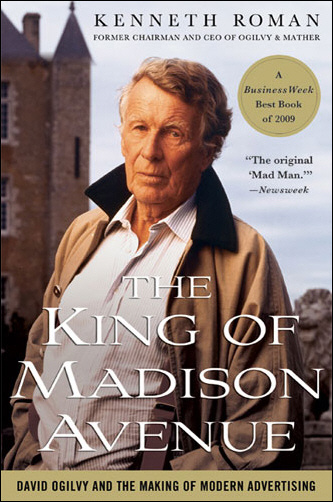

DAVID OGILVY: THE KING OF MADISON AVENUE

|

| According to David Ogilvy, “A good advertisement is one which sells the product without drawing attention to itself.” |

The man behind the Hathaway man, ‘good to the last drop’ Maxwell House coffee and a world-wide agency

By PAUL B. CARROLL, The Wall Street Journal, January 21, 2009

David Ogilvy (1911-99) had a grand life. He also had a boundless personality and a lot of fresh ideas, not to mention the luck of a booming postwar economy and the genius to take advantage of it. He helped transform the world of advertising – and generally in a good way, even for those of us who usually find advertising an annoying distraction from important things, like sports.

As described in “The King of Madison Avenue,” Kenneth Roman’s engaging biography, David Mackenzie Ogilvy’s life was writ large from birth. He grew up in England, but his background was Scots-Irish. His middle name, Mr. Roman reports, came from a family line that traced its wealth to 1494, when Hector Roy Mackenzie was awarded a 170,000-acre Highlands estate by King James IV of Scotland. A Mackenzie family member soon stirred up trouble when he became angry at a relative of his wife, who had only one eye: He returned her to her own family on a one-eyed pony, with a one-eyed servant and a one-eyed dog. A certain flair for making a point seems evident. Ogilvy’s ancestors mostly prospered until his father, a stockbroker, lost almost all his money with the outbreak of World War I.

Ogilvy won a scholarship to Oxford in the late 1920s but dropped out. He then spent nearly two decades as an intellectual dilettante, getting an education almost in spite of himself. In 1931, he drew on connections to land a menial job in Paris working in the kitchen of the Hotel Majestic’s restaurant – “the best in Paris at the time,” Mr. Roman says. Why go into restaurant work? It was the Depression, and Ogilvy explained to a friend that “a chef always has enough to eat.” Mr. Roman reports that Ogilvy “started at the bottom, preparing hot bones for a customer’s two poodles,” but soon moved up. Along the way, he learned the value of perfection. “He retold innumerable times,” Mr. Roman writes, “the story of his assignment to decorate the thighs of cold frogs with chervil leaves: ‘this was not cooking, it was jewelry, requiring good eyesight, a steady hand, and a sense of design.’” It was also a lesson in the value of perfectionism that would serve him well in advertising.

But before tiptoeing into the ad world, Ogilvy switched from working around ovens to selling them – the expensive Aga Cooker – door to door in England. In doing so, he became convinced of the importance of companies supporting the poor guy who peddles their products. It was a lesson he brought with him to the ad business when he went to work in 1935 at a London agency run by his older brother, Francis.

“Although he entered advertising to make money,” Mr. Roman writes, Ogilvy became interested, “obsessively interested,” in the business itself: “He said he had read every book that had been written on the subject.” Ogilvy soon moved to New York to explore opportunities in America and landed a job working for George Gallup’s polling firm, where he learned the value of research.

During World War II, Ogilvy’s sickly disposition kept him from serving in the military. He worked instead for British intelligence. After the war came the incongruous: Ogilvy moved to Amish country in Pennsylvania to try his hand at farming. The dashing young man with the aristocratic English accent adopted local customs, wearing high overalls with short straps, sporting a cropped beard and reading by candlelight.

Ogilvy’s wandering personal narrative finally took definitive shape in 1948, when he was 37. He established an advertising agency in New York, backed by his brother’s agency and another major English group. The agency, which became known as Ogilvy & Mather, succeeded almost immediately. Ogilvy took a little-known shirt manufacturer and made it instantly recognizable with “the Hathaway man,” who wore a rakish yet dignified eye-patch. After a single ad appeared in a single magazine, Mr. Roman says, shirt sales rose so fast that the ad had to be pulled until factories could catch up. It was Ogilvy who devised the slogan that said Dove soap was “one-quarter cleansing cream” and made Dove a leading seller around the world.

As the agency grew, Ogilvy reminded his staff again and again that advertising shouldn’t be boring, but it also shouldn’t indulge in what he called “the slippery surface of irrelevant brilliance.” Rather than trying to win awards for creativity, he said, ads should promote some key attribute of a product. The ferociously disciplined Ogilvy insisted on data. If someone asserted something about customer perceptions, the question was always: “How do you know?” Ogilvy became an early champion of the importance of brands.

The eccentric, hugely successful Ogilvy himself became something of a brand. He bought an ancient French chateau. He sometimes wore a dramatic black cape lined in scarlet. He so doted on his Scottish background that he was known to show up at formal occasions in a kilt. He might order a plate of ketchup or jar of jelly as a meal in a restaurant.

As Mr. Roman notes, Ogilvy’s primary gift was as a writer; he had less success once television ads made images more important than words, and he never really grasped the emotional power of music in ads. By the 1980s, he had faded into the role of elder statesman. Ogilvy was such a technophobe, the author says, that he used sharpened pencils instead of ball-point pens. The heart gladdens, then, with the thought that some of his ideas are back in vogue in an online age: The Internet fosters the direct selling that he championed, and it provides the sort of customer data that he demanded. The advertising agency that he built endures, as do memories of some of its most notable campaigns, such as Maxwell House’s “Good to the last drop” and American Express’s “Do you know me?” Thanks to “The King of Madison Avenue,” now we know David Ogilvy. Paul Carroll is the co-author of Billion-Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn From the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years.